"Poignant, cutting, witty, humorous, trenchant, optimistic and devastatingly honest, Bailey chronicles the profound and the mundane as he struggles to maintain his humanity in the face of war."

Garry Dow, Pomfret School

"Bailey was a literary magician—a man who plucked the right words from thin air at exactly the right moment, often as a grunt in mud and rain. His sense of humor was enviable."

Henry Zeybel, Vietnam Veterans of America

"It is worth a posthumous Pulitzer for non-fiction.

You and Maris can share the Nobel prize for peace."

Michael J. Olson, Ed.D.

Welcome to the Jungle

By Alex Bunten | The Charlotte News

"Private Loring M. Bailey Jr. was killed on March 15, 1970 in Quang Ngai fighting in the Vietnam War. He was from Stonington, Connecticut, and was only 24 years old. In the “Remembrances” section below his name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website, John Wilson, his platoon leader, recalls the exact time it happened: “I was standing there with him discussing our defensive options. We stood in the same area while discussing the options. . . and as I walked away, there was a booby-trap explosion that killed Loring but just threw me to the ground. To this day I don’t know how or why I survived and he did not.”

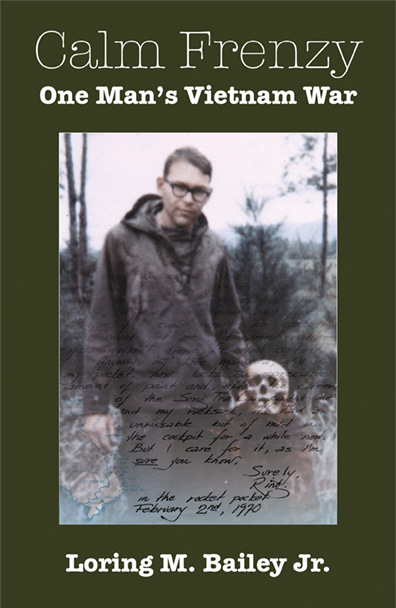

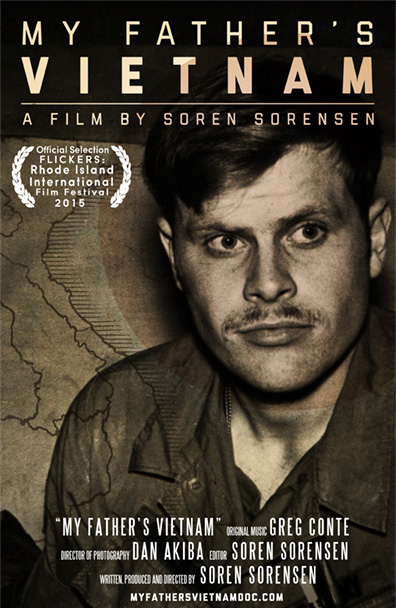

Although Ring, as he was called, didn’t make it home, his words live on in a soon-to-be-released book, Calm Frenzy: One Man’s Vietnam War. The book will be released on Veterans Day, November 11, at the Main Street Landing Film House, Burlington, alongside a new award-winning documentary film from Soren Sorensen called My Father’s Vietnam, which is in part about Loring and his relationship with Soren’s father during Vietnam.

Calm Frenzy is a series of edited letters to Loring’s wife, Maris Bailey, his parents, Loring Sr. and Dorothy, his brother-in-law, Rik Carlson, who works at the Little Garden Market in Charlotte and a close friend—the same people who helped compile the book.

The letters, mostly given without dates or addressee, paint a disjointed but candid picture of Vietnam, from basic training to a “360 degree front,” through the eyes of a curious mind and a gifted writer.

Loring writes at the start of the book, “Am I hyper-critical or does it just seem that everyone here would give his back teeth to get to New York City (without having to give up the Chivalay Impala and its stars and bars front license plate). What a sad state to preserve its rights so well and laugh so long at hair half as lengthy.”

Loring’s letters are full of wit, dry humor and sharp commentaries on everything from the subjective experience of organized religion to a detailed analysis of the aerodynamic tendencies of an M16 bullet.

He adopts a duckling named “Duckly” in one letter and questions the frequency of civilian mutilation in the next. As the commanding officer’s radiotelephone operator, Loring was often in charge of calling in the helicopter strikes that led to the latter. He struggles with this and many other facets of war but somehow maintains an even-keeled voice for his readers—drenched from 100 percent humidity or monsoon rain, he wrote whenever he could.

Although positive through many of his letters, the mental hurdles of war hit hard with Loring, especially when he attempts to call his wife for the first time: “Only an eccentric would run around screaming with a light machine gun under his arm. Granted. Only an eccentric could enjoy it, let it roll off his back, not react to it, relax and carry on a normal conversation with his fiancé a matter of hours later. There is no single definition of normalcy—it’s a statistically derived momentary constant which encompasses the infinitude of behavior.”

An articulate writer and deeply humane soul trapped in an inhumane place emerges from the pages this book. Just as the medical profession is occasionally blessed with a writer who has a keen eye for a story amongst daily suffering, such as William Carlos Williams or Anton Chekhov, so is the military for the experience of living as a soldier. For obvious reasons, however, solider writers are often more limited in their working time frame. Writing to his wife, Loring considers this, “We never said much about the hard possibility of my not returning from Vietnam, mostly because I plan to return, and under my own power; but each of the military vignettes in a letter makes that possibility more real for you.”

Loring would have been 70 years old on October 24, 2015."

Alex Bunten

"Loring (Ring) M. Bailey was my, ex-husband, David and my friend whose letters from “Viet Nam” to us, his wife, parents and others are thoughtfully written. This is significant to recognize considering the conditions from which he was writing. When he wrote by flash or candle light from extremely uncomfortable, wet, muddy and bug infested environment, with the screaming sounds of war surrounding him, I am reminded most Americans were safely home, barely satisfied to watch the nightly news and to receive our daily “Nam” death counts from Dan Rather. We watched the news like some today, watch reality shows. Ring’s experience and perspective provide an added intensity to the sorrow and grief of young lives lost in war and especially in an unnecessary one. For me, his writings unintentionally shame us because in the chaos of war Ring retained his humanity.

The following Haiku (Japanese style poetry) I wrote for Memorial Day and thought it was fitting to repeat here.

Memorial Day

White cloud in blue sky

Passes quickly beyond view

I remember you"

Yvette Dion Toohey

Calm Frenzy:

"At long last, I just finished reading Calm Frenzy. It is so many things at once: a compelling anti-war statement, depicting the gut-wrenching bleakness of war seen through the eyes of a young man just beginning his life's journey; an indictment of the specific pointlessness and cruelty of the Vietnam conflict; the story of the loneliness and isolation of one young soldier being propelled along by forces beyond his control to participate in an almost unreal, but life-threatening, experience; a glimpse at the inner soul of a man trying to reconcile and understand disparate emotions--love, loyalty, duty to kill, respect for life--and expressing that struggle in often forlorn letters home. The letters reveal Loring's innate intelligence and sensitivity. You cannot help but be impressed by his writing ability (for such a young man) and wonder what he might have produced had he survived the war. At one point, he mentions that the letters are written down and sent without review or edits--an impressive feat.

I have re-read a few times the handwritten letter that is reproduced on pages 145 through 151. It could make you cry. He sounds like a drowning man who is struggling to maintain his connection to a now-distant world and people who were once his mainstay and proof of his very existence and are now fading away or falling beyond his reach. He wonders whether, if he survives, he will ever actually return to that existence. What a burden for a 25-year old man! This must have been very difficult for his parents to read when editing the letters.

Even knowing the tragic outcome, I was constantly hoping that this ending could be avoided. There was a deafening silence on page 173 when the letters end and his final sentiment is "To be remembered is an honor, and the whole of my object". And then silence.... It was good of you and others to publish these letters and allow others--even strangers like me--to honor Loring by remembering him. "

—PAUL J. DION

By Alex Bunten | The Charlotte News

"Private Loring M. Bailey Jr. was killed on March 15, 1970 in Quang Ngai fighting in the Vietnam War. He was from Stonington, Connecticut, and was only 24 years old. In the “Remembrances” section below his name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website, John Wilson, his platoon leader, recalls the exact time it happened: “I was standing there with him discussing our defensive options. We stood in the same area while discussing the options. . . and as I walked away, there was a booby-trap explosion that killed Loring but just threw me to the ground. To this day I don’t know how or why I survived and he did not.”

Although Ring, as he was called, didn’t make it home, his words live on in a soon-to-be-released book, Calm Frenzy: One Man’s Vietnam War. The book will be released on Veterans Day, November 11, at the Main Street Landing Film House, Burlington, alongside a new award-winning documentary film from Soren Sorensen called My Father’s Vietnam, which is in part about Loring and his relationship with Soren’s father during Vietnam.

Calm Frenzy is a series of edited letters to Loring’s wife, Maris Bailey, his parents, Loring Sr. and Dorothy, his brother-in-law, Rik Carlson, who works at the Little Garden Market in Charlotte and a close friend—the same people who helped compile the book.

The letters, mostly given without dates or addressee, paint a disjointed but candid picture of Vietnam, from basic training to a “360 degree front,” through the eyes of a curious mind and a gifted writer.

Loring writes at the start of the book, “Am I hyper-critical or does it just seem that everyone here would give his back teeth to get to New York City (without having to give up the Chivalay Impala and its stars and bars front license plate). What a sad state to preserve its rights so well and laugh so long at hair half as lengthy.”

Loring’s letters are full of wit, dry humor and sharp commentaries on everything from the subjective experience of organized religion to a detailed analysis of the aerodynamic tendencies of an M16 bullet.

He adopts a duckling named “Duckly” in one letter and questions the frequency of civilian mutilation in the next. As the commanding officer’s radiotelephone operator, Loring was often in charge of calling in the helicopter strikes that led to the latter. He struggles with this and many other facets of war but somehow maintains an even-keeled voice for his readers—drenched from 100 percent humidity or monsoon rain, he wrote whenever he could.

Although positive through many of his letters, the mental hurdles of war hit hard with Loring, especially when he attempts to call his wife for the first time: “Only an eccentric would run around screaming with a light machine gun under his arm. Granted. Only an eccentric could enjoy it, let it roll off his back, not react to it, relax and carry on a normal conversation with his fiancé a matter of hours later. There is no single definition of normalcy—it’s a statistically derived momentary constant which encompasses the infinitude of behavior.”

An articulate writer and deeply humane soul trapped in an inhumane place emerges from the pages this book. Just as the medical profession is occasionally blessed with a writer who has a keen eye for a story amongst daily suffering, such as William Carlos Williams or Anton Chekhov, so is the military for the experience of living as a soldier. For obvious reasons, however, solider writers are often more limited in their working time frame. Writing to his wife, Loring considers this, “We never said much about the hard possibility of my not returning from Vietnam, mostly because I plan to return, and under my own power; but each of the military vignettes in a letter makes that possibility more real for you.”

Loring would have been 70 years old on October 24, 2015."

Alex Bunten

"Loring (Ring) M. Bailey was my, ex-husband, David and my friend whose letters from “Viet Nam” to us, his wife, parents and others are thoughtfully written. This is significant to recognize considering the conditions from which he was writing. When he wrote by flash or candle light from extremely uncomfortable, wet, muddy and bug infested environment, with the screaming sounds of war surrounding him, I am reminded most Americans were safely home, barely satisfied to watch the nightly news and to receive our daily “Nam” death counts from Dan Rather. We watched the news like some today, watch reality shows. Ring’s experience and perspective provide an added intensity to the sorrow and grief of young lives lost in war and especially in an unnecessary one. For me, his writings unintentionally shame us because in the chaos of war Ring retained his humanity.

The following Haiku (Japanese style poetry) I wrote for Memorial Day and thought it was fitting to repeat here.

Memorial Day

White cloud in blue sky

Passes quickly beyond view

I remember you"

Yvette Dion Toohey

Calm Frenzy:

"At long last, I just finished reading Calm Frenzy. It is so many things at once: a compelling anti-war statement, depicting the gut-wrenching bleakness of war seen through the eyes of a young man just beginning his life's journey; an indictment of the specific pointlessness and cruelty of the Vietnam conflict; the story of the loneliness and isolation of one young soldier being propelled along by forces beyond his control to participate in an almost unreal, but life-threatening, experience; a glimpse at the inner soul of a man trying to reconcile and understand disparate emotions--love, loyalty, duty to kill, respect for life--and expressing that struggle in often forlorn letters home. The letters reveal Loring's innate intelligence and sensitivity. You cannot help but be impressed by his writing ability (for such a young man) and wonder what he might have produced had he survived the war. At one point, he mentions that the letters are written down and sent without review or edits--an impressive feat.

I have re-read a few times the handwritten letter that is reproduced on pages 145 through 151. It could make you cry. He sounds like a drowning man who is struggling to maintain his connection to a now-distant world and people who were once his mainstay and proof of his very existence and are now fading away or falling beyond his reach. He wonders whether, if he survives, he will ever actually return to that existence. What a burden for a 25-year old man! This must have been very difficult for his parents to read when editing the letters.

Even knowing the tragic outcome, I was constantly hoping that this ending could be avoided. There was a deafening silence on page 173 when the letters end and his final sentiment is "To be remembered is an honor, and the whole of my object". And then silence.... It was good of you and others to publish these letters and allow others--even strangers like me--to honor Loring by remembering him. "

—PAUL J. DION

Calm Frenzy:

Welcome to “Books in Review II,” an online feature that complements “Books in Review,” which runs in The VVA Veteran, the national magazine of Vietnam Veterans of America.

This site contains book reviews by several contributors, while other reviews appear in each issue of The VVA Veteran. Our goal is to review every newly published book of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry that deals with the Vietnam War or Vietnam veterans. Publishers and self-published authors may mail review copies to:

Marc Leepson

Arts Editor, The VVA Veteran

Vietnam Veterans of America

8719 Colesville Road

Silver Spring, MD 20910

"Deploring the deep-seated dependency of Vietnamese on American aid, Loring M. Bailey Jr. wrote: “I’m enough of a youthful socialist to admit that not everybody can pull themselves up two hundred years by the bootstraps, but there’s such a thing as burdensome assistance. Enough. As the oriental sun sets gently over the snipers and touches its last golden rays to the olive Claymore mines, we bid adieu to Vietnam, land of mystery and mangled civilians.”

A booby trap killed Bailey on March 15, 1970, five months after he arrived in Vietnam at LZ Liz, near Chu Lai, and joined the Americal Division. Spec 4 Bailey had been a radio-telephone operator for both his platoon leader and company commander during what was to be an eight-month tour to finish his enlistment. Under the battalion’s policy, companies spent three weeks in the field and then one week at Liz.

Loring “Ring” Bailey died at the age of twenty-four, but his spirit lives on in Calm Frenzy: One Man’s Vietnam War (Red Barn Books, 175 pp., $15.95, paper). The book is a collection of letters that Bailey wrote to his wife, parents, and three best friends. Chip Lamb adapted the letters into a stage play before they became the basis for this book.

Bailey was a literary magician—a man who plucked the right words from thin air at exactly the right moment, often as a grunt in mud and rain. His sense of humor was enviable. For example:

“Just a dreary way to spend a hot, moist night, sitting, listening to your rifle rust.”

“I have a new fantasy—I pretend that I’m a Belgian mercenary and this isn’t my war, I just work here.”

After he adopted a duckling: “When he made his pitiful little squeaks, I agreed with him.”

To his wife, Maris: “You’re nice to love and hard to be away from, better than Dinky Toys and bigger. You must be real.”

Through Bailey’s eyes, we see a Vietnam War in which the American quest was futile, yet he persevered. He found a close parallel between the Americans in Vietnam and the British in the Revolutionary War. To wit: “We’re really having asses made of ourselves and paying well to have it done.”

Bailey’s reflections on his activities contained a philosophical tone mixed with touches of poetry and surrealism. His crisply written, sometimes convoluted, scenarios challenge a reader’s imagination and lead to unexpected conclusions.

He seldom spoke directly of combat. His greatest concern was for civilian casualties, particularly women and children. Yet Bailey foreshadowed his own death by noting: “Three of our third platoon people were killed by a booby trap while setting up for an ambush; one lived nearly a whole, precious, peaceful day, afterwards.” And soon thereafter: “More booby traps and such in evidence now.”

The book provides no account of Bailey’s death.

When I turned the final page, I grew teary eyed. I believe Ring Bailey would agree that he qualified as a poster boy for “The Waste of War.” He died just when he was beginning to live—like all the other young KIAs of Nam."

—Henry Zeybel

Hard Copy, 19.95, In Stock, Free Shipping

(U.S.Only)

EBook, $10.00

instant ebook here

Production began with a 2006 conversation between the filmmaker and his father, Peter Sorensen, who enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1968, a year when American troop levels in Vietnam were growing at the same rate support for the War on the homefront was shrinking.

“For my generation, sons and daughters of the ‘baby boomers,’ enlisting in the military has always been a choice,” said Soren Sorensen. “So, 40 years later, the idea of enlisting during the Vietnam War, in a divisive political climate not unlike what we’re seeing now, seemed to me sort of inconsistent with common sense.”

He added, “I was a bit naïve.”

The film features the stories of two men Peter Sorensen served with who were killed in Vietnam in 1970. For first-time filmmaker Soren Sorensen, the production process—which included shoots in Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, and Washington, DC—was an educational experience and a chance to get to know his father better.

“I came to realize that guys like my father didn’t really have a choice,” he said. “The romantic hindsight fantasy of burning your draft card and going to Canada had consequences related to your family, community, and financial situation that made it all but impossible.”

Sorensen continued: “Add to that the World War II generation looming large in history and culture. I think people wanted to live up to their parents’ expectations.”

The filmmaker says the process gave him a deeper understanding of the military and strengthened his relationship with his father.

“How could it not?” he said. “When you fly across the country and interview a complete stranger in Arizona about his experiences in Vietnam and he says, as my father says, ‘I’ve never had a conversation like this before,’ you realize just how silently Vietnam Veterans have carried the physical and psychological burdens of that war.”

He added, “Not only do you learn a tremendous amount, but you also gain an overwhelming sense of respect and gratitude.”

Peter Sorensen, the filmmaker’s father and one of the film’s primary subjects, said, “The film is more than the story of a father and a son. It's emblematic of the deleterious and ripple effect armed conflicts such as the Vietnam War have on entire families and ultimately the nation.”

The production turned out to be a multi-year odyssey for Soren Sorensen—who also produced, wrote, and edited the film—and Director of Photography Dan Akiba.

“Dan was the one who encouraged me to shoot the interview with my father in the first place,” said Soren Sorensen. “If it wasn’t for him, I might not have made the film at all.”

Featuring never-before-seen photographs and 8mm footage of the era, My Father’s Vietnam sheds new light on a disturbing chapter of American history that continues to deeply impact those who lived through it.

"My Father's Vietnam" is a powerful and gripping story---a worthy testament to complex lives and impossible choices made by young people coming of age while the world was in flames. These accidental heroes---soldiers, resisters, the women who waited and worried---emerge as fully human beings thrust into situations not of their making, struggling to make sense and create meaning out of chaos. This is a dazzling documentary and a necessary addition to the chronicle of the Viet Nam years.

Bill Ayers, author of Fugitive Days

"The horror, the horror of it all' came home, it didn't just stay in the war zone. 'Calm Frenzy,' the book, along with 'My Father's Vietnam,' the movie, strips war to the bone and tells you what history books and battle stories can't tell you.

They expose the chaos of politics mixed with misbegotten war, any war, and the veterans who fought it. There is no glory, there is no honor, there is never justice, and there never is a winner in any war. What endures forever is the pain, the pain of it all.

A "must" for all children and grandchildren who want to understand what is probably hidden or hard to figure out about a parent who was there.

So, who am I to say this? Michael J. Olson, Ed.D.; North Vietnamese Linguist, Combat Veteran with 4 USAF Air Medals plus 2 1/2 years in the war theater, and Top Secret Cryptology cleared COMMINT voice intercept processing specialist. I was in it deep, dark and within the blackness.

I hate what I know. I can't forgive self-proclaimed patriots who thought, and think now, that ANY war we have initiated in this lifetime are just or warranted. They are not. They propogate and spread disaster for many generations to come, just like this generation is discovering in the current debacle of Iraq II, and once again many wish to shake hands, be grateful for service, but still ignore veterans.

"When will they ever learn, gone to flowers every one."

"I can’t recommend it more highly as the best ‘war’ movie I’ve seen since Apocalypse Now as far as capturing all of the crazy emotions."

Michael J. Olson, Ed.D.

Film Tells the Story of the Vietnam War with a Local Connection

by SCOOTER MACMILLAN, 5/24/19